#21/25: hard doesn't equal worthwhile

on resonant frequencies and trusting difficulty over your own preferences

One reason I wanted to study engineering physics, and I was indeed swayed by its info session sales pitch, was its promise of breadth. Among other things, it required me to take electrical and mechanical engineering, math, and physics courses. I’d learn what I liked and what I didn’t! I looked forward to the self-discovery this process would yield.

I thought only good could come out of understanding my preferences, but having things I liked and didn’t like made me feel defective. As an example, I quickly learned I enjoyed math but felt less strongly about mechanical engineering. In hindsight, a response to this information could’ve been: you like math! Okay cool! Enjoy!!! But instead of just letting myself like what I liked, I focused on the problem at hand: there was something I didn’t like, and that meant there existed a personal deficiency I had to address. You don’t like mech. That’s like, bad!!! No worries: in due time, you will LOVE mechanical engineering. Passion would come with experience. I just knew it.

Years later, math was still interesting and mechanical engineering still wasn’t. I decided this was a discipline issue: I wasn’t trying hard enough, which is why I wasn’t good enough at it. If I were good at mechanical engineering, I would like it.

Was that really true, though? I wasn’t any better at math than I was at my mech courses. Math did not come easily to me. It was challenging and frustrating—but it was also interesting, and so it was also fun. Mech, on the other hand, felt like running through molasses—and that somehow became its whole value proposition. I didn’t enjoy it and I saw no future where I was a mechanical engineer, but at least I found it so hard that there was no way I wasn’t growing, right? The more bitter this food is, the better it must be for me. The harder this workout feels, the more I must be getting out of it.

Growth or not, by the end of my degree, my battle against my own preferences spiralled into chronic internal questioning that all pointed to there being something wrong with me. It didn’t help that I was around people who were so into these particular topics that they went on to grad school while I went straight to work. This made comparison easy: there was no way I actually liked math. You like math. Math? You don’t even understand what’s going on. Why are you pretending? If you like it so much, why aren’t you thinking about PhD programs? Not liking mechanical engineering was a character flaw. How do you not enjoy understanding how things work? You must really hate the physical world.

So I wanted to think about line integrals recreationally and not study turbulent flow at all. Was this a crime? I mean, look. If you teleported back to my childhood and told my parents that I’d grow up to like math, they’d probably jump for joy. SHE LIKES MATH!!!! Should we tell everyone? Should we throw a party? Should we invite Terence Tao?

The problem was never math or mech. The problem was, as always, me, and how I couldn’t trust myself to like the right things. This distrust bleeds into the rest of my life, where I keep a running laundry list of preferences titled “Things I like that make me feel unreasonably(?) bad about myself.” This list includes items such as:

Open fifth chords.

Thinking about consumer tech.

My bubble tea sugar/ice level choice.

The problem is this: it’s hard to accept preferences when you don’t trust their source. It’s hard to accept what you like when you don’t trust yourself. This is how I end up cascading through a thought flow chart that looks like this:

Do you like this thing?

No → something is wrong with you <3

Yes → something is wrong with it <3

and therefore something is wrong with you <3

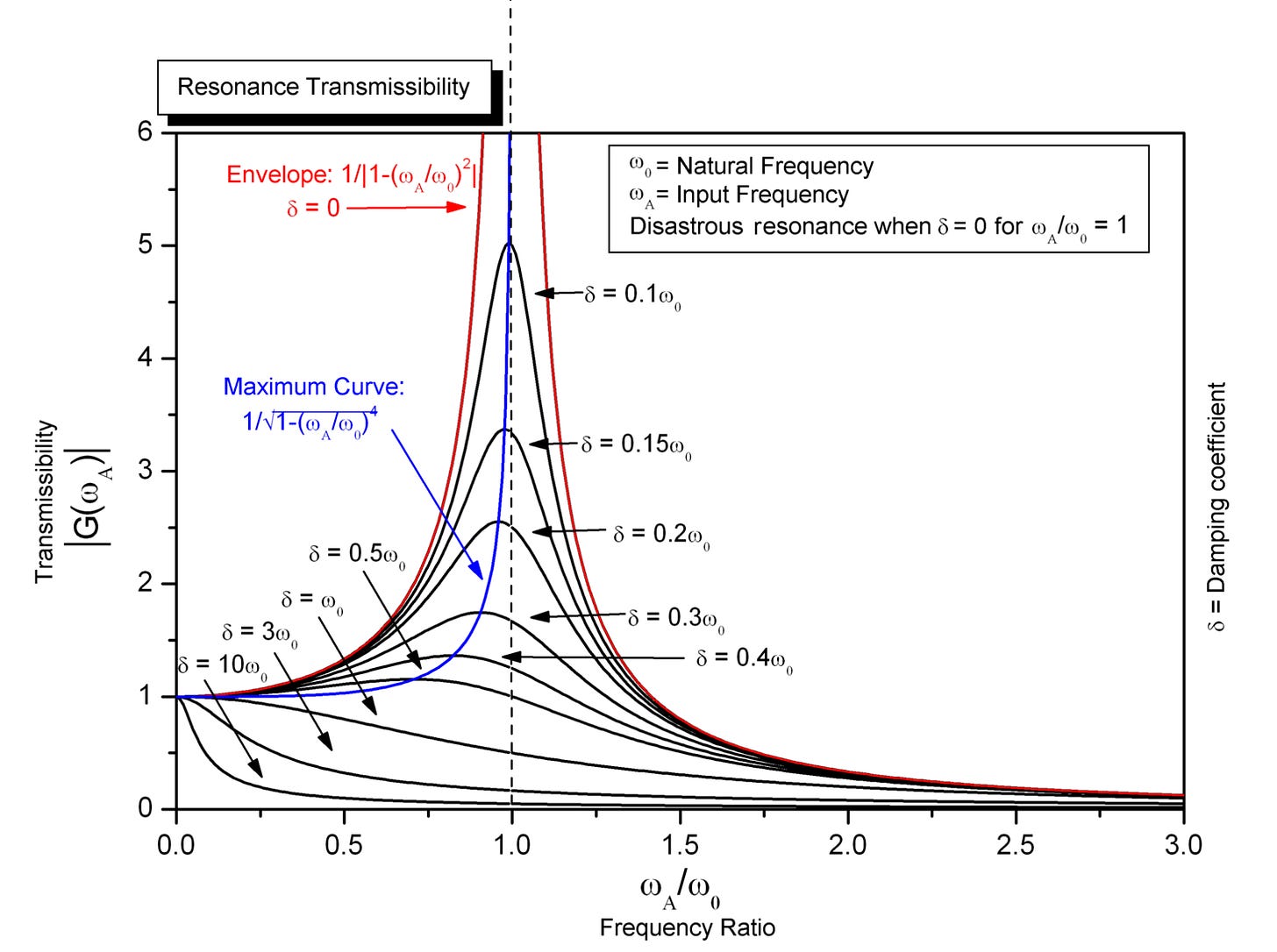

I clearly have preferences, despite the anguish they bring me. Why must I have this tuning?! A second-year lecture on RLC circuits and resonant frequencies offered comfort about having a particular tuning at all.

The concept is that systems have natural frequencies they tend to oscillate at. When an external force is applied to the system, some frequencies, close to the system’s natural frequency, are resonant. These resonant frequencies make the system’s oscillations stronger. Other frequencies can be so destructive that they cancel out the system’s oscillations entirely. Over time, as the system changes, the natural frequency can shift too.

I was like: how beautiful that systems have things that resonate with them. Maybe I do too.

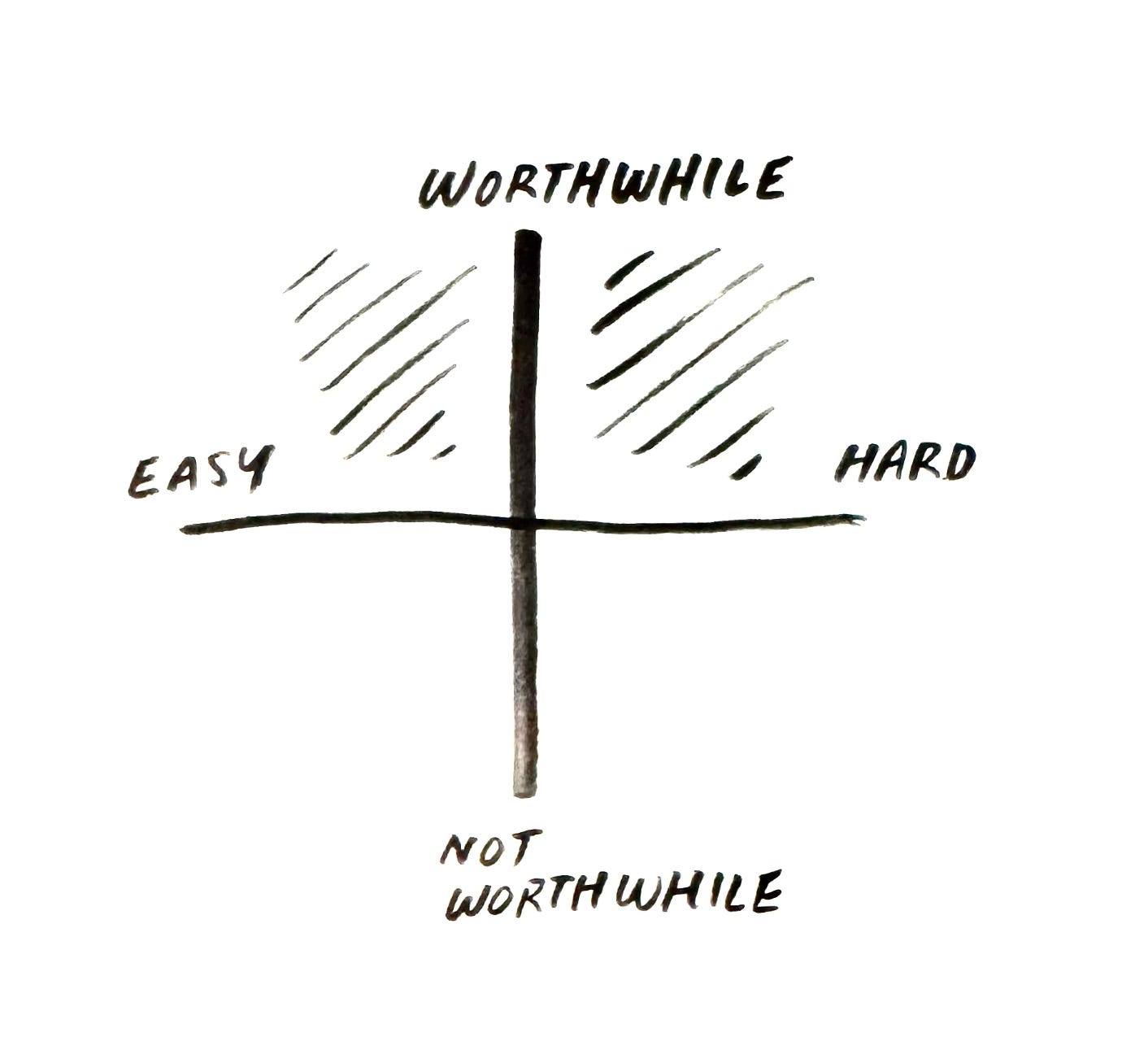

I clearly experience resonance. I just couldn’t trust what resonated because I didn’t trust myself, and therefore enjoyment was suspicious. If something felt natural to me, clearly I wasn’t growing. Growth is a good thing that I should be optimizing for, right? And I must be growing if the task at hand feels really, really hard. Hard became a stand-in for worthwhile.

What worthwhile means to me here is something I want to invest myself in. I naturally want to invest myself in things that resonate—but because resonance is personal and I didn’t trust my own judgment, I trusted difficulty instead. Difficulty is personal too, and yet I used it as objective proof of value. The trap I fell into was that some worthwhile things are hard, and not all hard things are worthwhile.

Remember: what feels “worthwhile” and what feels “hard” are both subjective and personal. That means that in your own life, whatever it looks like for you, there is worthwhile hard and there is suffering-to-prove-a-point hard. It’s easy to assign virtue to “doing hard things,” and if you do them, there’s a guaranteed outcome: at least you did something hard! But what I keep returning to in my writing is this desire to grow into myself—and that includes knowing I can do hard things, but not only that. And there’s that trap again: the temptation of arbitrary difficulty as a fallback form of growth when you’re afraid to confront what you actually want.

So when something feels hard, how do you know what kind it is? I think you cut through the noise and identify resonance by feeling it. My theory is that the natural frequency is love. Love is resonant, fear is anti-resonant. Love swells, fear dampens. When I look at mechanical engineering, I see resonance that faded with time. At first I approached it with curiosity, needing to know I could persevere and give it—and myself—a fair chance. This was love. But years later, I was holding on out of fear that letting go meant I was giving up, and giving up was that moral failing I was so afraid of. I was so afraid of myself that I thought pushing through the anti-resonance would transform me, make me better, make me finally worthwhile. What this did instead was consume my time and emotional space, leaving less room to grow into what I actually did love. There was so much more curiosity I could’ve chased down that I didn’t.

I don’t know much but I do know this: I would rather have my life be shaped by love than fear. When I unravel the knots, tease out the threads, and arrive at the core, what one essence do I find: fear or love? When I really let myself sit with the feeling, I've always known which one felt more true.

This is what I know too: I need to know what happens when I follow love.

I often think about alternate timelines and who else I could’ve been. Still, I don’t regret the decisions I've made—even when I question them on aimless walks, at night alone, and whenever I stare out the window and see something, anything that reminds me of who I’m not and the ground falls from beneath me—when I know the decision was resonant with love. When the decision is resonant with love, the decision is resonant with me.

💌 this is piece #21 in “if only i had a fourier transform for this feeling”, a series of reflections on what i learned while studying engineering physics in university. thank you for following along <3